So You Want to Build a Hearthstone Deck…

Building and refining Hearthstone decks is hard. It takes high levels of skill to even figure out where new, powerful opportunities reside. This is the “big” problem of deckbuilding, as it covers the larger outline and gameplan of your deck. It helps determine everything that is to follow.

However, once you have the general picture of your deck in mind there will be a great many smaller problems that, in many cases, take longer to solve. You need to figure out which and how many synergy cards to include, which stand-alone cards are worth playing, which “packages” of cards can and cannot be ignored, and how you can execute your intended strategy in the face of other players trying to beat you. These are all the “small” optimization problems.

What makes these matters incredibly difficult is that Hearthstone is a high-variance game. Your deck might lose a match, but was that because it was built poorly or was it because your opponent drew well? Perhaps there was a random card generated that changed the entire course of the match, which is unlikely to happen again. Personally, I have had back-to-back days where I played an identical deck for 30 games each time, ending with a 67% win rate on the first day and a 37% on the second.

This makes assessing your decks and card choices incredibly difficult. Not only you do have 30 cards to assess, but you’re trying to assess all of them at the same time in an environment that’s constantly uncertain and shifting.

Put plainly, there is no way we can, as humans, fully optimize our decks with the information we are capable of collecting personally. While we can get reasonably close at times, our personal data will never be sufficient to decisively determine how favored deck A is against deck B in general, let alone figure out whether card A is 0.5% better than card B, on average. No one is even capable of doing so (with appropriate amounts of confidence. Some players may still be inappropriately confident in their conclusions). Instead, we have to rely on our intuitions and emotions about how well everything is performing, what should stay, what should go, and what should replace it.

We can be good at these problems, but we’re far from perfect.

Modern Problems Require Modern Solutions

As Hearthstone is quite variable and our brains are not designed to detect the statistical patterns in that noise accurately enough to make the best conclusions, we have created a series of tools to aid us in our quest for the perfect lists.

Sites like HSreplay.net are incredibly useful because they can aggregate the data collected from thousands of players who are using these cards as well, allowing us to see what works and what doesn’t. This is a staggering amount of information that we cannot even come close to collecting on our own. By pooling our personal data into a collective, however, we end up with something much greater than the sum of its parts. Instead of relying on intuitions, we can see in plain numbers how often decks have been winning, at what ranks, over what time, and how many games result in a win when a player has mulliganed into, drawn, or played any particular card.

Now it’s not as simple as just reading the numbers and thinking you’ve learned all there is to know about them. Data analysis on these sites is a skill just like any other, and we need to interpret it properly to get the most out of it (for a quick guide on some tips to do so, see here). Nevertheless, it’s easy to get started using data.

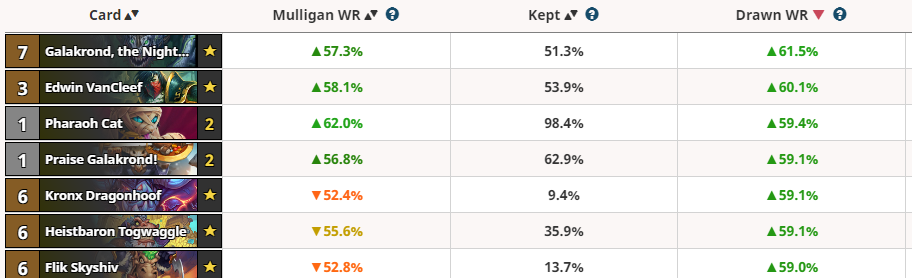

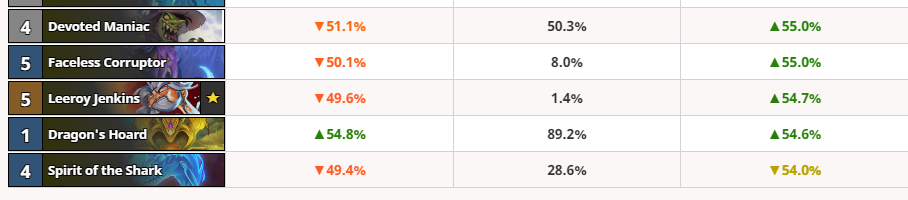

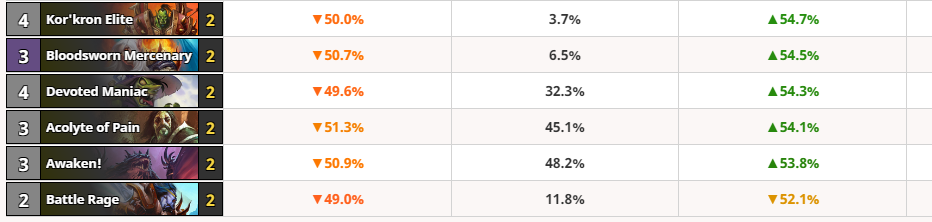

One quick and useful metric to look at is “Drawn WR” which is the winrate of the deck for games when that card is drawn at any point. Looking at this metric can help you sort out the weakest cards in your deck.

Now there will always be a “worst” card in your deck – there has to be – but one of your goals during deckbuilding should be to ensure your worst card isn’t a clear liability; not much worse than other cards in the deck. If you see a worst card that is, say, 0.1% worse than your next worst card, that’s not a big deal. If you see a card that is 1-5% worse than your next worst card, that’s a sign something has likely gone wrong and some choices should be reevaluated.

This part can be exceptionally tricky, but not just because data isn’t always easy to interpret. It can instead be tricky because we are very good at tricking ourselves. As the famous line goes in science, you must not fool yourself, and you are the easiest person to fool. Remember those intuitions and emotions I mentioned early? Some people can convince themselves that a particular deck or card is good, and once you have done that it can be hard to unstick that idea from your brain, even in the face of a lot of contradictory data.

In fact, the smarter the person you are, the more dangerous these incorrect intuitions and feelings can become. This is because smart people are, to be blunt, very good at being stupid. Smart people (and good players) are very good at thinking up plausible-sounding justifications (because they’re smart/good) for choices that ultimately end up being bad. They can feel more confident in ignoring other people’s data because it doesn’t match their high-skill intuitions.

This was the case when it came to Spirit of the Shark not so long ago. Many players were convinced the card was good, despite mountains of data saying it was bad. It was always the worst card in any list playing it; a fact which remains true even today, even in Highlander lists.

If you need a testament to how bad this card is, in decks with 30 separate cards, Shark is worse than the other 29 by a decently-wide margin. (That is, of course, assuming you don’t do something like play an even worse card that no one would rightly touch, like Kidnapper). I say all that as someone who was rooting for the card to be good. I’d love to have more fun and powerful tools at my disposal, but the card just made every deck it touched worse.

Despite that, many players – both good and bad – came the conclusion that the card should stay in the deck, created plausible-sounding justifications for why its performance wasn’t good when looking at the data, and went on to lose more games than they otherwise needed to because decks without the card outperformed the decks with it (even if many people will still deny it to this day).

What Causes Sticky Intuitions

To understand why at least some of these intuitions get “stuck,” despite ample data they’re bad, we can consider another contemporary example to pick up some possible similarities: Battle Rage.

If we look at modern Galakrond Warriors, you’ll be hard-pressed to find lists that don’t run this card. Despite that frequency of play, Battle Rage remains the card with the lowest drawn win rate in the deck, and not by a small margin, either: the card usually wins 2-3% less than the next worst card when it gets drawn at any point. This doesn’t seem to change in decks that run the new Risky Skipper either, which could be premium synergy. It’s a consistent pattern of underperformance seen across tens of thousands of games.

So why does the card stick around in decks? Part of the reason is surely inertia: most people aren’t building decks; they’re simply copying lists that have them. But there’s more to it than that, as many people who seek to win as much as possible do legitimately seem to believe the card is powerful.

One important thing to note is that – much like Spirit of the Shark – Battle Rage sometimes creates huge, powerful moments. There will be games where you draw 5 cards for 2 mana and come back to win a game you thought was lost. Other times, you might see your opponent fire off that same play, chain a big Battle Rage into another big Battle Rage, and suddenly refill their hand. These are big moments that don’t happen within the usual power curve of the game (see Arcane Intellect for what an on-powercurve draw card looks like), and they create equally large memories of them. One can even imagine all the huge, possible plays they might make with the card and get excited about how it will work in the deck. It makes intuitive-sounding sense that the card would be good.

Do you know what doesn’t create similarly large memories and anticipation? Sitting on a Battle Rage you cannot play to any real effect for many turns because you either don’t have enough damaged targets or you cannot use the mana to draw without falling too far behind on tempo. Maybe you just Battle Rage for one. Maybe you get a big Battle Rage, but it’s after the card sits dead for 6 turns and then it’s too late. It’s a much less memorable experience, and yet it’s a much more common one.

Further, you might come to think that Battle Rage is good because your opponents always seem to get good ones off, don’t they? That’s probably true, but that’s also probably because your opponents simply won’t play the card if it’s bad most of the time. If the card sucks and does nothing for them, they’ll probably make any play they can besides Battle Rage. You won’t even know it’s in their hand being useless. This can leave you with a biased set of memories for how the card plays out in the game because you literally see if more often when it’s good than you do when it’s bad (not unlike how you usually only see Leeroy Jenkins played when it’s going to kill you; not when it’s inefficient and useless).

While it might make intuitive sense that Battle Rage could be good, it also made sense to some people that putting the Bazaar Burglary Quest in a Galakrond Rogue shell could be good too. Not because they were trying to complete the quest, but rather because they could play the “if you have a quest” payoff cards. This felt like you’re doing something sneaky, powerful, and intelligent to many. It could create some high-roll moments with Questing Adventurer or Edwin VanCleef (like Shark, like Battle Rage…). It made good sense to them.

It also threw about 3-4% of the Galakrond Rogue deck’s win rate into the garbage.

Getting Unstuck

Breaking from these intuitions won’t be easy. I cannot promise that I can even do much to help you besides raising awareness of their existence. The one piece of advice I can at least offer is to change your perspective on the questions you ask yourself.

When it comes to Battle Rage, Spirit of the Shark, and other similar cards, don’t just ask yourself about what their possible uses are, or what their best cases can be. You might not even want to ask yourself what their worst cases are, as I assure you that you’re capable of assuming those worst cases won’t happen very often and the best cases will happen regularly. Instead, ask yourself the following question: what pattern of data could prove me wrong? If you think a card is good, ask yourself what might change your opinion. In the event you’re unable to provide a good answer – that there isn’t much that could change your mind or that you couldn’t just rationalize away – there’s a good chance you’re dealing with a sticky intuition. It doesn’t mean your intuition is wrong necessarily, but it does mean you should be careful around it.

And remember: there’s nothing unusual about being wrong. Everyone is wrong several times a day. Don’t be ashamed of being wrong: celebrate the opportunity it allows you to find out how to be better.

This article seems to be more about power level of cards in specific decks, than PL in general. Where true deck building skill lies is realizing when a card synergies enough with your deck AND against the majority of opponents to warrant inclusion. For example mct is usually a bad card. But in a draw heavy quest shaman with battlecry synergy, it was often a good inclusion, only because that was a token heavy meta. Shark was very strong in pogo rogue, not so in galakrond. I went 42-26 (61.76% WR) with a homemade pain warrior in the meta of embiggen, gala rogue, gala warrior and face hunter (from rank 5 to 2). Battle Rage was extremely strong in that deck, because my minions were cheap, almost always damaged and it countered many meta decks. Not so much in galakrond warrior. (I can write a whole article about that [HoF’ed] deck alone).

About “high/low skill cap”, I’ll give a macro example because it’s more famous. The principles apply to specific card inclusions as well though. Pogo rogue at its peak, had below average WR on HSreplay because it was a deck that needed to adapt its playstyle according to the matchup and required a lot of complex decisions. To many players ran without maxing its potential, lowering its supposed WR. Embiggen druid was the exact opposite. Buffed overall WR because it has a very linear gameplan. And can be successfully piloted by lesser skilled players.

By the way, I don’t consider myself a top tier player. Just someone with a decent understanding if HS principles. Did I never reach legend because I only have time for 100 games per season, max? Or because I never will, even during this COVID-19 pandemic, now that I have more time? I’ll probably never know.

One of the guys said good stuff. HSreplays is statistics from all players. But only a small percentage is good. And it is almost a tech card. If you play against aggro, it is very bad. Today this card singlehandedly won me a couple of games when I was in a tough spot or when I had bad matchups.

We should be careful when we use the available data in HSReplay. The DRAW WR is based on lots of games from lots of players, both good and bad players. Looking just at the numbers to identify good and bad cards would not consider different skill levels from players and different matches those players played. Let’s suppose most players don’t know how to effectively use battle rage, it would impact the WR of the card. Most of the times it is obviously when to play a card, but some times is not… spirit shard for example, you gotta have a plan before you play it, you can’t just play it on turn 4 and see what happens on turn 5… but most players might do that, and lose the game… we can’t tell just looking at the numbers.

Im not saying spirit shark or battle rage are good… Im talking about numbers.

This has been an argument put forth to justify these cards a lot; the idea that they’re “High-Skill-Cap Cards.” These are cards/situations that people regularly misplay, but get a lot better when they’re don’t misplay them.

That’s a case that could be true, but the issue we run into a lot is that people just say, “Well, it’s a high-skill card,” and leave it at that, rather than testing their idea that this is true. If you want to read more thoughts about that, feel free to check out this post: https://reddit.com/r/CompetitiveHS/comments/bwhx2i/the_myth_of_the_highskill_cap/

What’s interesting about that idea is that many people classify things as “high skill” when they have a lot of different potential options, like Battle Rage and Spirit of the Shark. It’s intuitive as for why this is the case, but there are many smaller decisions that are overlooked as high-skill as well, such as keeping or not keeping certain cards in the mulligan (Hooktusk was my go-to example way back when, but apparently now Warriors are over-keeping Felwing in their opening hand and gassing out because it, according to the VS people).

Really nice article.

Something that I hope everyone who is struggling to make it to legend that actually reads this comment thinks about: you can’t win every game of hearthstone no matter how hard you try.

This article talks about how you might lose games simply because your opponent drew good, or they got a random card that changed the course of the game. This happens a lot, and you will lose those games, and then later you will win games where you get the lucky draw. It’s just the nature of probability, you win some you lose some. The difference between the best players and the tier below them is that the best players don’t let 1, 2, or 5 bad luck games in a row affect their mindset. If you consistently make the right plays you will be rewarded over time, you will win more games and make it to legend. It’s when you let the good luck of your opponent affect you that you begin to tilt and lose 5-10 in a row back to the ranked floor. It’s ok if it takes 75 games to get to legend from rank 5, but no one ever takes 25 games to get to legend from rank 5, so don’t let one loss affect your play and keep up the focus.

I’m actually glad there are cards like Spirit of the Shark and Battle Rage that actually weaker than they feel. The meta for Hearthstone has enough sameness as-is; there should be “traps” and “baits” to encourage some variation and experimentation.

I like that these cards encourage experimentation as well. It is another facet of player skill that separates the good from the best.

What I appreciate a little less about it is how people can adopt the mentality of, “I don’t care about the data,” when it conflicts with those feelings. It’s a mindset that’s better to avoid and not spread to others

My question is: Draw WR is really useful indicator? I mean, in a fast cycle deck you draw a lot of dead cards that barely comes into play. In Ex. Handlock or Quest Druid or Control decks you play for hand size and have options in hand so you need to draw maybe “bad” cards. If you look at stats in this kind of decks could be wrong or innacurate at least!

Fast draw should affect to all cards In your deck, so I doubt that it can become draw wr in a bad indicator

In cases where you draw all your cards regularly, drawn WR gets wonky, yes. Most decks/games don’t result in this issue, thankfully.

Really good article. I catch myself thinking this way sometimes. The key thing is most people are really good at seeing reward (the crazy high roll moments), but terrible at perceiving risk (the rest of the time the card is completely dead).

This kind of thinking is something I struggle with on ladder. The key thing is to take a step back and realize that Casual mode is there for a reason. It allows you to play with all the crazy high roll synergies without consequence. It is why I my time there when I just want to relax without any stress from being on ladder.